Let's fast forward a few years now; I'm not a child anymore…and I'm still not keen on having deadly substances in our cabinets or cupboards. But let's face it, the tools are not the culprits for mishaps; it's mostly operator error. FYI, lye can be found in the following household products:

- Aquarium products

- Clinitest tablets (urine testing reagent)

- Drain cleaners

- Hair straighteners

- Metal polishes

- Oven cleaners

- and more…

When working with lye, be sure to take these necessary precautions:

So, I'm online the other day and I notice a post on Facebook by our friends at Homestead Survival. They posted an image from a Do-It-Yourself tutorial on a site called SoapDeliNews.com. I must admit that after reading the post I am willing to give lye another shot (although all safety precautions will be taken). It's now clear to me that soap making is a huge deal because if you follow a trusted informational source, it's fairly easy.

Here's a portion of Rebecca D. Dillon's original article:

Soapmaking can be a lot of fun and very rewarding. However, it's not something to just jump right into without first some research and understanding of the process. Not only are there precautions that need to be taken when making cold process soaps, but a failed batch can be a very expensive lesson.

Because of the many dangers associated with soapmaking due to the use of lye – also known as sodium hydroxide – and the plethora of information to be had, I recommend that you carefully research the process before starting out on your own. Details on where to obtain additional information will be included within this article.

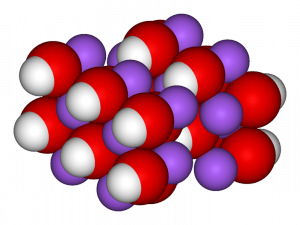

Soapmaking involves a chemical process in which sodium hydroxide (lye) reacts with oils to make soap. This process is called saponification. Because this process requires the use of lye, important safety precautions must be taken. Rubber gloves and safety glasses should be worn during the soapmaking process, and vinegar, which neutralizes the lye, should be kept on hand in case of an accidental spill or burn. In addition to the necessary safety equipment needed for your journey into making cold process soap, there is other required equipment you'll need to get started.

First and foremost you will need to acquire lye. Because without lye, there is no soap. The main components to make a true bar of soap are fat(s) – such as oils and butters – and an alkali – more commonly known as lye. You should be able to find lye in the plumbing section of your hardware store, at a local chemical supply store, or online. For those just getting started and without the need for a 50lb. bag of lye available from chemical supply stores, you can buy Roebic Heavy Duty Crystal Drain Opener in 2lb. containers at Lowe's stores. (It contains 100% sodium hydroxide also known as caustic soda.) Alternatively, Red Devil Lye can be purchased online. The brand doesn't really matter, but it must be 99% or more pure sodium hydroxide. (If you are local to Roanoke, VA you can purchase 50lb. bags of sodium hydroxide beads locally in 50lb. bags from ChemSolv. Just be sure to transfer your bag of lye to a plastic container or double garbage bag lined box that you can seal after opening.)

In addition to the lye, you'll also need a large pot for mixing the soap. I recommend a large stainless steel pot. What type of pot you use is up to you, however, your pot cannot be aluminum. Lye reacts badly with aluminum so remember to never mix the two. You'll also need an accurate scale to weigh your ingredients in either ounces or grams. You can use digital postal scale from an office supply store. Just be sure the scale is calibrated properly and can handle the amount of weight you will be using. You'll also need a thermometer or two to measure the temps of your oils and lye solution. And, you'll find that a stick blender – also known as an immersion blender – is your best friend in making soap. You can hand stir, but this method can take you hours over minutes and a stick blender also ensures even distribution of ingredients. And then of course there are the molds, soapmaking oils, and distilled water to be mixed with the lye.

There are several types of molds you can use to create cold process soap. You can purchase tray molds that are basically hard plastic molds that will create numerous bars of soap at once. These molds should be marked suitable for cold process soapmaking since the soap gets very hot during the saponification process. You can also easily build a mold from wood, with a bottom and four sides. This type of mold will produce a log of soap that you would then cut into slices. When using a wooden mold, you must line it with parchment paper to aid in easy removal of the soap. (Freezer paper is not a good idea as it melts to the soap and mold.) Lining your mold is sort of like wrapping a present except that you are wrapping the inside of the box rather than the outside. It takes some practice to get it right. The parchment should then be secured with tape to the mold. Alternatively, you can line your mold with plastic film or a plastic office sized garbage bag. Just be sure to tape the material to the top of the mold for easy removal. You can learn how to make your own wooden soap molds here. (You can also make silicone soap molds.)

Next, we're on to oils. The soapmaking oils are an important part of your soap. The types of oils you use will determine the properties that your soap will have. For example, three of the most popular soapmaking oils, especially for beginners, are olive oil, coconut oil, and palm oil. The olive oil helps create a moisturizing bar with a stable lather; coconut oil produces a hard, cleansing bar with a fluffy lather; and palm oil makes for a hard bar with a stable lather. Each of these oils has its own SAP (or saponification) value which determines how much lye should be used in the soap recipe for saponification to occur in such a way that it makes soap. Too much lye and you have an unusable bar of soap. Not enough and you could end up with a really soft soap with excess oil. A great source for learning more about the saponification process and the properties of various soapmaking fats & oils is Susan Miller Cavitch's book The Soapmaker's Companion. Her book also contains a great troubleshooting section and several of her own recipes. When creating your own recipes for soap, there are also a lot of additional free resources to help you with this process. Lye calculators, for example, will automatically calculate the amount of lye you need in a recipe based on the amounts and types of oils you plan to incorporate into your recipe. You can find multiple links to lye calculators by conducting a google search. Although I like to use the lye calculator at Majestic Mountain Sage. It is good practice to always double check the amount of lye in a recipe with a lye calculator if you are unsure of its source.

Continue reading the tutorial by clicking HERE.

No comments yet.